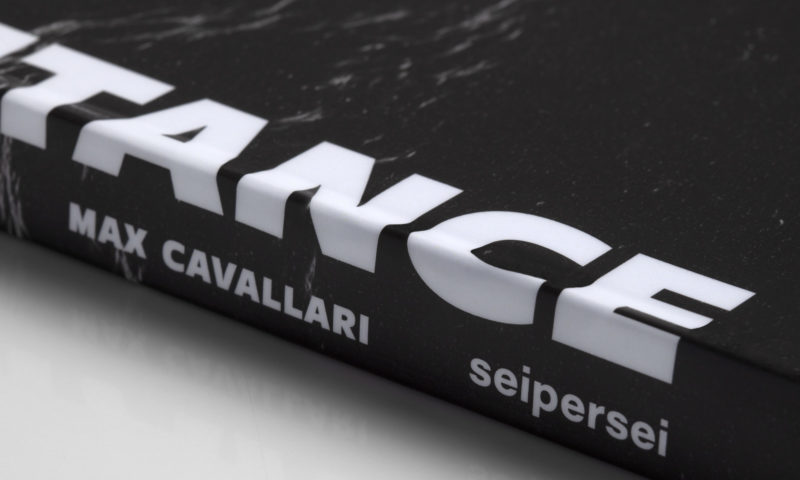

Our mission in photographs: “Acquaintance” von Max Cavallari

The book “Acquaintance – Search and Rescue in the Mediterranean Sea” by Max Cavallari documents in impressive black and white pictures our mission in October 2022, during which a total of 180 people were rescued. The photographer was on board the Humanity 1 and captured his impressions on camera.

The book is available here.

It turned out to be a life-changing experience. I was lucky enough to be on board the Humanity 1 as part of the crew for our second search and rescue mission in October and early November 2022. For nearly three years I had worked as the press and public relations officer for the humanitarian, non-governmental organisation SOS Humanity. I had always been based in the Berlin office, explaining the ongoing emergency situation in the central Mediterranean, the deadliest migration route in the world, to journalists and the public. I had described how it was for people fleeing from Libya in unseaworthy, overcrowded boats. I had regularly depicted the situation on board our rescue vessel with hundreds of survivors sleeping on deck, waiting for a place of safety to be assigned to the ship for them to disembark. Now, I was sailing myself, together with 28 people of all ages, nationalities and backgrounds. It felt like a great adventure on the one hand, and a huge weight of responsibility on the other. I knew that any time, an emergency situation could develop in which every move and every minute would decide between life and death.

More than a third of the crew were volunteers: the doctor, the nurse and the paramedic, the mental health expert, the human rights observer and a few others. A third of the crew were female. I was also on board one of our two RHIBs as a part of the rescue team. We try to have at least one woman on board the fast rescue boats, known as RHIBs, which approach a distress case first. Female survivors might feel more comfortable, and it also shows we are not the so-called Libyan Coast Guard, but rescuers.

One of the greatest fears of those who risk the dangerous crossing of the Mediterranean fleeing from Libya is to be intercepted and forcibly brought back by the heavily armed Libyans who make up this so-called Coast Guard, funded by the EU. Many fear this more than drowning. “It’s better to die in the Mediterranean than to die in Libya. In Libya, even your dead body isn’t safe,” 18-year-old Buba (name changed) from Gambia told me, after we had rescued him and 112 other people from a rubber boat which was already losing air. It was his third attempt to cross the Mediterranean: twice Buba had been intercepted and forcibly returned to Libya.

For the crew, getting ready for a rescue is a very tense moment. All of us were highly focused, from the captain to the cook to the photographer, glad to have practiced every step many times – in theory, in practical trainings, in the day and at night, in good and in bad weather, including the worst-case scenario: a mass casualty situation. Our photographer Max Cavallari was also on board of one of the RHIBs. His task was to document every step of each rescue. His photos are and will be of major importance for media who report on what is happening in the central Mediterranean, for SOS Humanity’s public relations such as reports, fundraising material, social media and our website. But like me, who wrote a blog for our website during my six weeks at sea, Max was simultaneously a rescuer. Had we encountered an emergency with several people in the water, he would have dropped his camera and just saved lives. Teamwork is what is most important on a rescue ship. Evacuating 113 people from a precarious rubber boat who are panicking because the so-called Libyan Coast Guard has suddenly arrived, requires perfect, professional cooperation. In this case, we were able to bring every single person, including a seven-month-old baby, safely on board the Humanity 1.

We knew that we could fully rely on every team member, no matter what. I was impressed how well this highly diverse team cooperated – and proud to be part of it.

We rescued 180 people from three boats in distress. We spent two weeks with them on the ship waiting for a place of safety. It was astonishing how not only the crew had grown together as a team, but also how close the relationship with the survivors became. When we were eventually assigned the port of Catania, Sicily, for disembarkation, a new, far-right government had just taken over in Italy. As a result, an unprecedented triage of the survivors was performed by authorities, leaving 35 of them on board. These adult men were classified as healthy and not in need of protection. Again, the crew did everything to solve this issue: the captain refused to leave port with those people on board, referring to the law of the sea. We filed a lawsuit and informed the Italian and international media. After three days and the beginnings of a hunger strike by the rescued people on board, they were able to leave the ship, too.

For the crew it felt strange to separate after six weeks and everything we did together. We had lived and worked so intensively on this limited space in the middle of the Mediterranean. Thanks to my fellow crew member Max Cavallari and his artistic photography, this lovely book gives a strong impression of why returning to our regular lives was not easy.