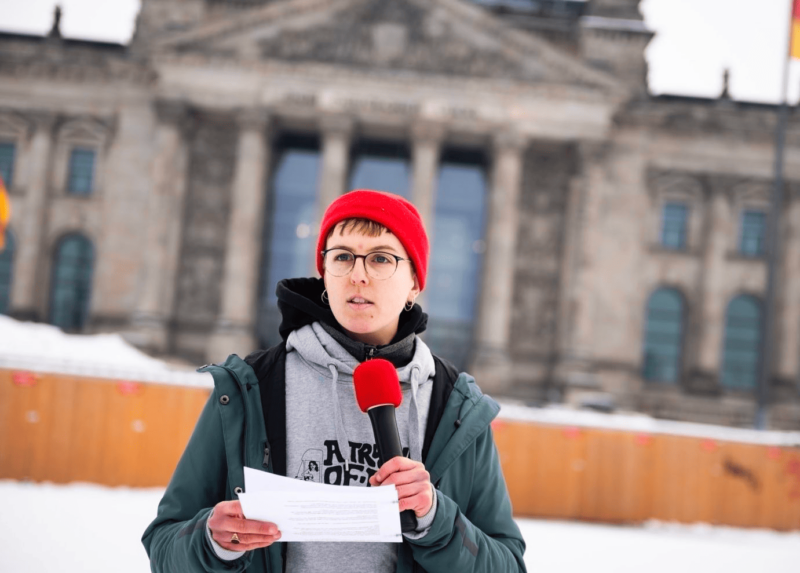

“It’s the structures that make people vulnerable.” A conversation with Caro from ROSA e.V.

Caro (33) has been active at ROSA e.V. for around a year and is currently in charge of political affairs. The NGO campaigns for safe spaces for ‘FLINTA*’ (females, lesbians, intersex, non-binary, trans and agender people) refugees on the move and in Germany. In this interview, she explains the special challenges these people face.

Why are safe places particularly important for FLINTA* people on the move?

First of all, it should be noted that refugee routes, conditions and accommodation in the camps are catastrophic for all refugees. This is clear and must never be forgotten when drawing attention to the specific challenges FLINTA* people face, so as not to create a gradation or hierarchy.

Yet FLINTA* people are exposed to different challenges and conditions. If you look at the camps in Greece, where we are also active, there are often many people in a small space. There is poverty, violence, drug abuse, very little privacy and poor medical and hygiene care.

None of this can be solved with ROSA’s Safer Space, but we nevertheless try to offer FLINTA* people a space where they can meet, where they can bring their children or leave them in childcare and where they can receive medical care. It is also always important to us that the Safer Space is a place where FLINTA* people can organise themselves, and that can cover a wide range of possibilities from meeting together, drinking tea, laughing and crying to workshops.

What makes it dangerous for FLINTA* people to flee?

There are conditions that make fleeing even more challenging and also more dangerous for FLINTA* people: just imagine being or becoming pregnant during the journey. This is an extreme challenge that requires rest, specific nutrition and medical care, which is not provided at any time on their journey and is also structurally withheld.

We have even heard reports from the camps in Greece that the women deliberately drink less, for example, so that they don’t have to go to the toilet because the hygiene conditions in the camps are so catastrophic. There are simply far too few sanitary facilities and these do not provide sufficient privacy because they are not shielded. This makes them places where sexual harassment is possible and – according to the reports – takes place on a daily basis.

The other thing is that women often have both childcare and family care responsibilities. Travelling with children restricts mobility. Then having to find a job in order to be able to feed yourself makes it even more difficult to flee.

The list of reasons is long. Ultimately, it remains to be said that women – especially when travelling alone – are even more at risk due to patriarchal capitalist structures. Women tell us about sexual exploitation and having to use their bodies as commodities to pay smugglers.

To what extent do the reasons for fleeing differ between FLINTA* people and men?

Here, too, the same reasons also exist. Of course, people of all genders are fleeing war, poverty and living conditions that do not allow them to live in dignity. Yet FLINTA* people face different challenges due to their gender and sexual orientation.

For example, men often flee to escape forced recruitment. This is a specific reason for fleeing that is more likely to apply to men or male-read people. For FLINTA* people, on the other hand, domestic violence, for example, is a more common reason. Others are: forced marriage, forced sterilisation, abortions, female genital mutilation, or, in general, the denial of human rights, including the freedom of movement, the right to education, the right to one’s own physical self-determination – all of these are reasons that primarily affect FLINTA* people.

What does the recent adoption of Germany’s so-called ‘Repatriation Improvement Act’ and the associated criminalisation of altruistic humanitarian aid mean for your work?

We have had to deal with this a lot. The law tries to criminalise the work of NGOs at the external borders. As ROSA does not work directly at the borders, but primarily in the Athens area, and our task is not to transport people, our current work is not at significant risk. This is a good thing, but we had to invest a lot of time and energy to find this out. We also had to rely on expert advice from lawyers to find answers to the question: “How can we move forwards?”.

That is exactly what this law does: it creates uncertainty and makes the work of NGOs difficult.

Quite apart from that, it is a disastrous message to criminalise humanitarian aid that is altruistic. If you think about it, you can see in which direction the law is heading.

How do you feel about these political developments?

Personally, it makes me angry and stunned, although unfortunately it is not surprising when you consider the political situation.

The good thing about it is that this law has enabled us to network much better with other organisations, such as search and rescue NGOs. Strong alliances can emerge from this, not only to observe incidents, but to take action, to be a voice for civil society and to unite in solidarity.

What are you demanding from politicians?

We never tire of demanding safe refugee routes for all people and at the same time structural solutions for the specific challenges and conditions for FLINTA* people. And, above all, we do not want our work to be dragged down by the right-wing any longer.

Statements such as: “We are pursuing a feminist foreign policy” are empty words. We have seen nothing of this so far. We demand actions that recognise and improve the situation, but at the same time do not portray FLINTA* people on the move exclusively as helpless and as victims, but also value feminist struggles and solidarity actions.

What is particularly important to you in relation to FLINTA* refugees?

What is important to me and to us is recognising specific needs and not just talking about women and FLINTA* and assuming that they are generally vulnerable.

It is important to understand that being particularly vulnerable does not depend on the person or gender itself, but that it is politically designed structures that make people vulnerable and that these must be combated.