In our life-saving work at sea, we always comply with applicable international law. According to this law, the duty to rescue at sea applies everywhere and to all ships equally. Coastal states must ensure that every person in distress at sea is helped. Subsequently, there is an obligation under international law to bring those rescued from distress at sea to a safe place on land as quickly as possible.

-

The duty to rescue at sea applies everywhere at sea and to all ships equally.

-

States must ensure that every person in distress at sea is helped.

-

People rescued from distress at sea must be brought to a place of safety.

Search and rescue is a duty

Under international maritime law, all ships anywhere at sea are obliged to provide assistance to people in distress. Rescue at sea is anchored in maritime tradition as a human duty and is recognised as customary international law everywhere at sea [1]. In addition, three international conventions regulate the coordination and implementation of maritime rescue: the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS, 1974) [2], the International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR, 1979), [3] and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS, 1982) [4].

Regardless of whether they are private merchant ships or state-owned military vessels, all ships and seafarers without exception are bound by the principles of search and rescue. All ships in the area are obliged to provide assistance to people in distress at sea. The only restriction is that the ships and their crews should not put themselves in danger during rescue operations. (SAR, Annex)

What counts as a maritime emergency?

A maritime emergency is when people on board a ship are in serious danger and cannot reach safety without outside help (SAR, Annex). Such an emergency situation exists, for example, if a boat is unable to manoeuvre, if the number of people on board exceeds the capacity of the ship or if there is a lack of rescue equipment such as life jackets. The following is a list of the criteria that constitute a maritime emergency [5]:

a request for assistance

the (un)seaworthiness of the boat (for high seas) and the likelihood that the boat will not reach its destination

the excessive number of people on board in relation to the type and condition of the boat

the lack of life-saving equipment and the fact that people are not wearing lifejackets

the availability of necessary supplies such as fuel, water and food sufficient to reach a safe place

the actual weather and sea conditions and forecasts.

The boats in which people seeking protection flee from Libya and Tunisia are not seaworthy and are usually dangerously overcrowded. In addition, those on board are not wearing life jackets. They are therefore considered a maritime emergency from the moment they leave the coast.

It does not matter whether people knowingly or unknowingly put themselves in danger, as international law prohibits discrimination. All people in distress at sea must be provided with assistance, regardless of their nationality, status or the circumstances in which they are found. (SAR)

What does maritime rescue have to include?

Maritime rescue involves rescuing people in distress at sea, providing them with initial (medical) care and bringing them to a place of safety. (MSC 155) [6] The rescue is therefore only complete when the survivors have reached a place of safety. At this place, the lives of the rescued persons must no longer be in danger and the fulfilment of their basic needs must be ensured. (MSC 167) [7] Disembarkation must take place as quickly as possible.

Distress at sea – states have a duty to coordinate

In order to ensure safety at sea, all coastal states are legally obliged to set up and operate an “adequate and effective search and rescue service” themselves or to join forces regionally to facilitate such a service. (UNCLOS)

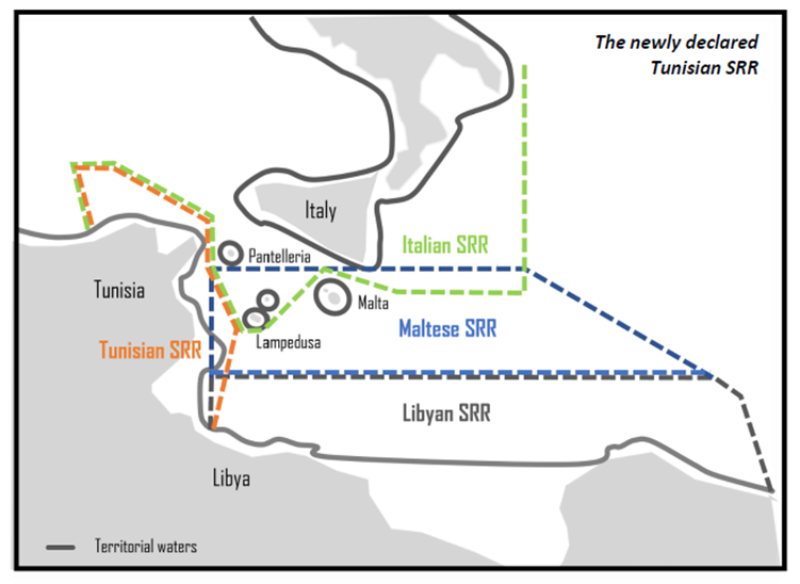

Thanks to the International Maritime Organisation, all territorial and international waters have been divided into search and rescue zones (SAR zones) and responsibility for these zones has been defined. The relevant coastal state is responsible both for coordinating maritime emergencies and for allocating a safe place for survivors. To this end, the coastal state must set up a Rescue Coordination Centre (RCC) that is able to respond to emergencies and coordinate rescue operations. This Rescue Coordination Centre must be equipped with suitable means of communication, in particular for receiving emergency calls. (SAR) Furthermore, it should be reachable around the clock and staffed by English-speaking personnel. (MSC 70) [8]

If a rescue coordination centre is informed of a distress at sea with an unknown position and it is not aware whether other centres are taking appropriate action, it shall assume responsibility until a competent rescue coordination centre is designated to fulfil the coordination obligation. (SAR) The first rescue coordination centre reached shall be responsible for coordinating the distress case at sea until the competent rescue coordination centre or another authority assumes responsibility. (MSC 167)

As soon as a rescue coordination centre learns of a distress case at sea, it is obliged to instruct the nearest vessel in the immediate vicinity to carry out the rescue, to facilitate a medical evacuation if necessary and, following the rescue, to quickly allocate a nearby safe place for the disembarkation of the survivors. (SAR)

The coordinating rescue coordination centre is obliged to appoint an on-scene coordinator. Until this appointment is made, the first ship to arrive in the search area automatically assumes the role of on-scene coordinator. The on-scene coordinator is responsible for the search and rescue operations if these tasks are not carried out by the rescue coordination centre. (SAR)

What constitutes a place of safety?

The rescue only legally ends when the survivors are able to go ashore in a safe place. At this place, the lives of those rescued must no longer be in danger and the fulfilment of their basic needs must be ensured. (MSC 167)

Furthermore, both the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR, 1950) [9] and the Geneva Refugee Convention (GRC, 1951) [10] stipulate that people may not be returned to a state with a precarious human rights situation (“non-refoulement principle“). This applies to ships of the EU and its member states as well as to private ships sailing under the flag of any state that is bound by these conventions. The guidelines of the International Maritime Organisation of the United Nations also stipulate that survivors in need of international protection should not be brought to a country where their life and freedom are at risk.

Would you like to learn more about the legal background of search and rescue? In our international law report from page 14 onwards, we have analysed the legal basis in more detail (in German), including references to the relevant laws.

[1] International Review of the Red Cross, 2016, available online here

[2] SOLAS, 1974, available online here

[3] SAR, 1979, available online here

[4] UNCLOS, 1982, available online here

[5] EU Regulation No. 656/2014, Article 9, available online here and UNHCR, IOM, OHCHR, UN Special Rapporteurs on Trafficking in Persons and Human Rights of Migrants, and Foundation for Humanitarian Action at Sea, 2024, available online here.

[6] MSC. 155(78), Annex 3.1.9, available online here

[7] MSC.167(78), Annex 6.12, available online here

[8] MSC. 70(69) 2.3.3, available online here

[9] ECHR, 1950, available online here

[10] Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, 1951, available online here